A reactive dog is not necessarily an aggressive dog. However, the unaddressed reactivity issue can quickly transform into aggression. Canine aggression is one of the most frequent problems in veterinary behavioral medicine, which in severe cases may result in relinquishment or euthanasia, so your attention to training becomes extremely important.

How Do We Recognize Reactive Dogs?

Reactive dogs are those that consistently overreact to everyday stimuli in the environment with heightened emotional or behavioral responses such as barking, lunging, growling, spinning, or freezing. Reactivity is not synonymous with aggression; many reactive dogs are primarily fearful or frustrated rather than intending to cause harm, but reactivity can escalate into aggression if not properly addressed.

Common triggers include other dogs, unfamiliar people, children, bicycles, skateboards, loud noises, or specific visual features like hats or beards. Some dogs show leash reactivity (reactive while on-leash but not off-leash), while others react in particular contexts, such as crowded spaces or during veterinarian visits. Research from the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine shows that causes of reactivity include genetic predisposition, inadequate socialization during critical early periods, prior negative experiences, and insufficient training or coping skills. Reactive behavior reflects an emotional state of over-arousal, either from fear (fight-or-flight) or frustration/over-excitement. Understanding this emotional basis can help you choose the most appropriate intervention strategies.

Reactive dogs require management and behavior modification tailored to their triggers and thresholds rather than punishment-based approaches, which can worsen fear and provoke more severe reactions.

How to Identify Triggers for Reactive Dogs

Identifying triggers requires careful observation across multiple environments and situations to find the specific stimuli that consistently precede the dog’s reactive episodes. Start by keeping a simple log book of walks and incidents to record:

- Time and location.

- The distance to the stimulus and the type of stimulus (dog, person, vehicle, sound, object).

- The dog’s exact behaviors (bark, lunge, stiffen, spin) and body language before and during the episode.

- The contextual factors, such as whether the dog was on-leash, tired, or distracted.

Observe whether the reaction from your dog is consistent across contexts or if it is context-dependent. For example, a dog may tolerate other dogs off-leash but become reactive to on-leash dogs, or react only in quiet environments when unexpected people appear. These patterns reveal whether the trigger is the physical presence, the unpredictability, the proximity, or the dog’s restricted ability to respond.

Use distance as a diagnostic tool. You can use it to determine the dog’s threshold by noting how close a trigger can be before the dog’s response escalates. With this information, you can gradually desensitize the dog to the stimulus and help them respond more calmly.

Combine these observations with information about the dog’s history, such as early socialization or traumatic events, to distinguish fear-based triggers from frustration- or resource-driven triggers. This understanding will help you make/develop/create the most effective behavior-modification plan.

How to Recognize Body Language Signs From Reactive Dogs?

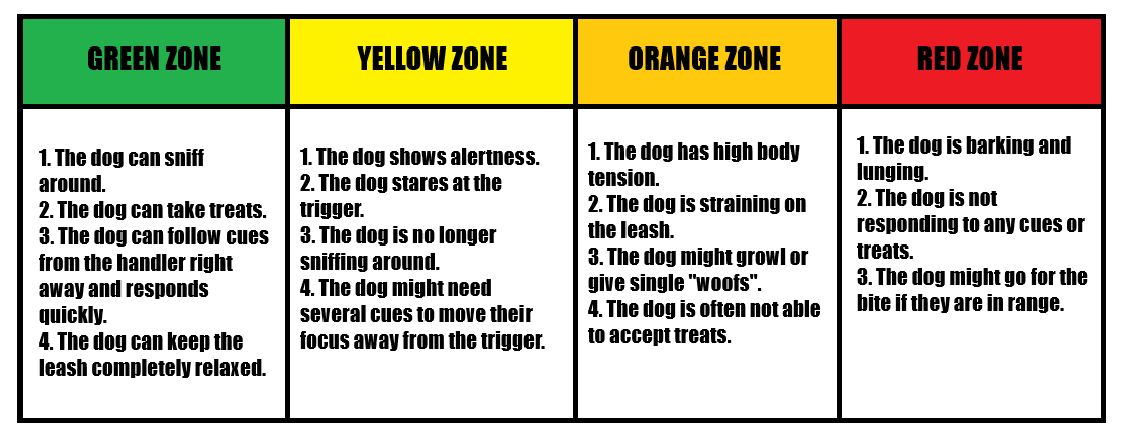

Recognizing body language begins with learning the dog’s baseline relaxed behaviors and then noting changes that indicate escalating stress or arousal. Early stress signals include subtle cues such as lip licking, yawning, turning the head away, increased sniffing, freezing or focused stare, and slight body stiffening. More obvious body language cues include raised hackles, growling, barking, lunging, intense pulling on the leash, spinning, or a hard, fixed stare with raised and pointed ears.

A reactive dog will usually show an elevated attention to their trigger by focused gaze and pointing their ears to the stimulus. This will typically be followed by increased body tension, repetitive or frantic movements, and pacing. The next escalation may involve vocalization/barking and out-of-control reaction, where the dog no longer responds to their handler’s cues.

Recognizing and responding to early signs of out-of-control reaction allows the handler to distance themselves from the trigger and ensure their dog is relaxed and under control. It’s essential to watch for individualized cues. Every dog has unique “tells” such as flicking one ear, tapping front paws, or a particular facial expression. Train yourself to spot those before the dog reaches their out-of-control reaction threshold so you can manage distance and apply counter-conditioning or engagement games effectively. We elaborate on this below.

How to Do Behavior Adjustment of a Reactive Dog

Begin with management to reduce exposure to high-intensity triggers and prevent repeated rehearsals of reactive episodes. Choose quiet walking times, avoiding dog parks, using space cushions, and employing emergency cues (like a practiced U-turn) to remove the dog from imminent high-trigger situations.

Build foundational skills by developing a reliable focus/engagement command, practicing basic cues, and building motivation by using high-value rewards (boiled chicken, cheese, carrots, strawberries, and blueberries). It is important to provide sufficient physical and mental exercise, including sniff/decompression walks and enrichment, to reduce baseline arousal.

How to Do Desensitization

Start by approaching the trigger and stopping at a safe distance. The safe distance is where your dog notices the trigger, and they remain vigilant but non-reactive. Spend time with your dog near the trigger for their reactivity and try to play games like tug-of-war or fetch. Practicing commands is also a good idea. The idea is to make the dog tolerate the trigger and gradually build a calmer response to that.

How to Do Counter-Conditioning

Reward looking at the trigger and then looking back to you when called. Slowly reduce the distance to the trigger and make sure your dog is calm and relaxed. If they get agitated, increase the distance again. Do this for 2-5 minutes. Then end the exposure to the trigger by walking away and doing something your dog enjoys. Repeat this exercise until your furry friend reliably turns their attention to you when called. Every time your partner looks at the trigger, wait for them to look away from it or look at you. Use “Good boy/girl!” with an excited voice and give them a tasty treat for “disengaging” from the trigger.

Seeking Help is OK

If the guidance above does not lead to improvement, please consult a veterinary behaviorist or qualified force-free trainer for complex or high-risk cases. Working with a dog trainer can help with:

- Exercising in environments that are more controlled and appropriate.

- Working with other people and dogs to simulate triggers and avoid high-stress situations in public spaces.

- Guidance on prioritizing skills and things to improve.

- Bridging the gap between theory and practice on what can work for your particular case.

- Building your dog’s skills based on feedback from the trainer.

- Troubleshooting and adapting when training does not go according to plan.

Rehabilitating Reactive Dogs – Does It Work?

Managing and rehabilitating reactive dogs is often successful when approached systematically with force-free, evidence-based methods, realistic goals, and consistent long-term effort. Many dogs show substantial improvement in frequency and intensity of reactive episodes, gain coping skills, and can be walked more calmly in various environments. Keep in mind, there is no “cure” for ractivity or a 100% effective treatment program that fits all dogs. The outcome depends on the severity of the reactivity response, the underlying cause, and the owner's consistency.

Success factors include accurately identifying triggers and thresholds, preventing repeated high-intensity encounters early in training, building solid engagement and focus skills, and using desensitization and counter-conditioning at sub-threshold distances. Owners who pair management with behavior modification, monitor body language, adjust expectations, and seek professional help when needed typically achieve meaningful, lasting improvements in quality of life for their dog and themselves.